I just returned from a successful weekend road trip. I say successful because of the 5 hours that I personally drove; I only missed one exit, resulting in a short 10-minute detour from our destination. For those of you who know me this is a huge accomplishment. In recent years, I rarely make it to a destination without multiple U-turns. The worst was when my husband woke from a nap in the passenger’s seat to find that I had traveled three quarters of the way around the Washington D.C. loop and was heading back north on our trip from New York to North Carolina! I emphatically insist that if the co-pilot stayed awake during the entire trip these things wouldn’t happen. But the truth is that once I get on the highway and point my wheels between the dotted white lines, the driver in me goes on autopilot and my mind travels elsewhere toward solving the problems of the world.

Okay, maybe I am exaggerating. Truthfully, I could be thinking about grocery shopping, my next bulletin board, or our new puppy, but over the last 2 years I have also had a recurring philosophical debate with myself – “What geometric shape best represents physical education in today’s society?”

This internal discussion began after reading Knowledge/Skills and Physical Activity: Two Different Coins, or Two Sides of the Same Coin? (Blankenship, 2013). In it, Bonnie questions the direction of physical education. She refers to physical education and physical activity as being two sides of the same coin. The image of physical education as a coin with two sides got me thinking about my beloved Springfield College Triangle and the Humanics Philosophy.

“It starts with Humanics, the age-old Greek ideal of the balanced individual. We believe, as did the ancient Greeks, that a person’s emotional, intellectual and physical lives are interconnected. The Humanics philosophy calls for the education of the whole person-in spirit, mind, and body-for leadership in service to humanity.”

I took this quote from the Springfield College website. It’s the institution where I received both my master’s and my bachelor’s degree. With the philosophy comes Dr. Luther Halsey Gulick’s inverted equilateral triangle, a symbol that represents the ideal. Dr. Mimi Murray, Professor of Exercise Science and Sport Studies, recently interpreted the triangle for me as follows: The sides of the equilateral triangle represent the emotional, intellectual, and physical sides of a person; the spirit, mind, and body. Murray adds, “Gulick also believed that through the equal and harmonious development of the body and mind, which lead up to and support the spirit across the top of the triangle, one would also develop spiritually. The circle around the triangle is probably as important if not more so because it symbolizes the whole person … a circle is complete with no beginning or ending … consequently one cannot separate mind and body as we have vainly tried to do for centuries in education!”

I’ve used this triangle as a model for teaching physical education for my entire career. While our educational system has created a category directed toward teaching to the physical domain, I’ve always attempted to do so by educating the whole child including their spirit, mind, and body.

When the new NASPE standards (Couturier et al, 2014) were launched last summer, I began to contemplate how these standards fit into the triangle.

- Standard 1 – The physically literate individual demonstrates competency in a variety of motor skills and movement patterns.

- Standard 2 – The physically literate individual applies knowledge of concepts, principles, strategies and tactics related to movement and performance.

- Standard 3 – The physically literate individual demonstrates the knowledge and skills to achieve and maintain a health-enhancing level of physical activity and fitness.

- Standard 4 – The physically literate individual exhibits responsible personal and social behavior that respects self and others.

- Standard 5 – The physically literate individual recognizes the value of physical activity for health, enjoyment, challenge, self-expression and/or social interaction.

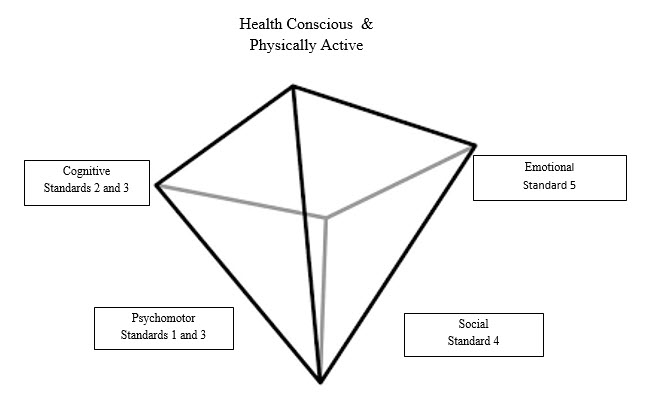

The first standard belongs to the physical domain (body). The second standard fits in the cognitive domain (mind). The third asks for knowledge and application of skills suggesting both cognition and physical movement (body and mind). The fourth and fifth standards seem to fit the social and emotional domains (spirit).

As I grow as an educator and not just a physical education teacher, I appreciate the concept of balance more and more. As an educator I embrace the inverted triangle as it is, however, because our educational system demands that we departmentalize, I feel the need to create a physical education specific depiction of Gulick’s philosophy. First, I would expand his two-dimensional triangle representation into a three-dimensional inverted pyramid. This pyramid would depict the balancing of our physical education standards in an attempt to support the development of a health-conscious, physically literate, active adult.

There’s much to consider if the goal of physical education is to prepare students to become lifelong, healthy, physically literate, active adults. We must teach our students the principles of health and fitness, help them acquire the skills needed to move in variety of activities, give them opportunities to learn the social rules needed to participate effectively, and create situations that provide positive emotional experiences. If physical educators fail to follow this balanced teaching approach the likelihood of our students achieving these goals is surely diminished.

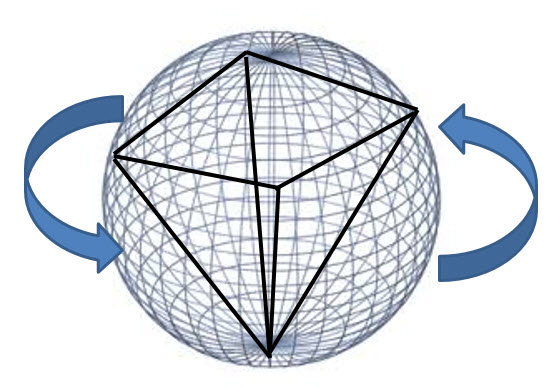

Likewise, I would change the two dimensional circle that represents the whole child into a three dimensional animated sphere representing how physical education teachers have to roll, spin, and bounce from one domain to another in order to educate the whole student. The sphere may come to a rest periodically for a cognitive activity, and then bounce into a physical challenge. Teachers may create thought-provoking social situations then immediately slow things down to assess students’ emotional response. Teaching to the whole child is never a static, rote application of a written lesson plan but a constant assessment of student needs and reassessment of which domain needs to be focused on to address those needs.

While it’s quite possible to teach physical education effectively without worrying about geometric shapes, the intellectual journey I took to make one has helped me come to terms with where I stand in the evolving field of physical education. As a society, we may not be following the ancient Greek philosophy of Humanics exactly the way it was intended to be implemented, but I hope our ancestors would appreciate my attempt to adhere to the overlying principle of balance.

Phew! Now, maybe I can focus on the exit signs!

References

- Blankenship, Bonnie. “Knowledge/Skills and Physical Activity: Two Different Coins, or Two Sides of the Same Coin?” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, Volume 84, (Issue 6), 2013.

- Couturier, Lynn, Stevie Chepko, and Shirley Holt/Hale. National Standards & Grade-Level Outcomes for k-12 Physical Education. Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2014. Print.

- “Humanics Philosophy.” Retrieved from http://www.springfieldcollege.edu/welcome/humanics-philosophy/index#.VKnQCyvF-So