SCOLIOSIS:

TO EXERCISE OR NOT

by: Andrea

S. Ruark

Will exercise or spinal manipulations

prevent scoliosis from progressing?

Will these things correct already diagnosed

scoliosis? Are there any activities

a child or adolescent with scoliosis

cannot do? Defining scoliosis, classifying

scoliosis, and learning about different

methods of treatment can help answer

these questions.

According

to Stopka & Todorovich (2005), “Scoliosis

is a lateral curvature, accompanied

by vertebral rotation of the spinal

column (p57).” Many schools perform

routine scoliosis screenings in middle

and high school. A forward bending test

is used to look for symmetry between

the left and right side of the spine.

An observer stands behind or in front

of the student while the child bends

forward toward their knees and toes. According

to Stopka & Todorovich (2005), “Scoliosis

is a lateral curvature, accompanied

by vertebral rotation of the spinal

column (p57).” Many schools perform

routine scoliosis screenings in middle

and high school. A forward bending test

is used to look for symmetry between

the left and right side of the spine.

An observer stands behind or in front

of the student while the child bends

forward toward their knees and toes.

The observer examines the region between

the upper thoracic and lumbar regions

of the spine. If the observer sees anything

that appears asymmetrical, the child

is referred to their primary physician

for further diagnosis. Examples of asymmetrical

findings include one shoulder higher

than the other, a “winged”

scapula,

or a rib hump on one side, uneven waist,

leaning to one side, and one hip higher

than the other (Staff, 2007).

Scoliosis curves can be identified

as functional or structural. Functional

curves resolve when the cause of the

curve is rectified (Lonstein, 1999).

Examples include leg length discrepancies

that are fixed with a heel lift, or

ruptured discs that are repaired through

physical therapy or surgery. Structural

curves have three main causes; congenital

scoliosis, neuromuscular

scoliosis, or idiopathic

scoliosis (Lewis, 2008).

Congenital scoliosis is present

at birth, and means the vertebrae did

not form correctly or the ribs fused

during fetal development. Neuromuscular

scoliosis is caused by muscle weakness

or paralysis due to disease. Possible

disease causes are cerebral palsy, muscular

dystrophy, and polio. Idiopathic

scoliosis is from an unknown cause

and includes the majority of adolescent

scoliosis diagnoses. According to Yochum

& Maola, “Of all causes, an

inherited genetic defect appears to

play a significant role with up to 30

percent of patients having another family

member with significant scoliosis (p14).”

However, this genetic link does not

appear to determine the progression

or severity of the curve (Yochum D.C.

& Maola D.C., 2008).

A

physician typically uses three diagnostic

steps. These include a physical examination

of the spine, shoulders, hips, and legs,

including the forward bending test,

x-rays, and possibly an MRI.

The doctor uses the x-ray to calculate

the degree of the spinal curvature,

and determines the treatment based on

this, the child’s age, and where

the child is in their growth spurt.

An MRI is only used if the x-ray shows

something abnormal, or the physical

exams shows neurologic changes (Lewis,

2008). A

physician typically uses three diagnostic

steps. These include a physical examination

of the spine, shoulders, hips, and legs,

including the forward bending test,

x-rays, and possibly an MRI.

The doctor uses the x-ray to calculate

the degree of the spinal curvature,

and determines the treatment based on

this, the child’s age, and where

the child is in their growth spurt.

An MRI is only used if the x-ray shows

something abnormal, or the physical

exams shows neurologic changes (Lewis,

2008).

After diagnosing scoliosis, the physician

describes the curve according to its

shape, C-or S-shaped; the location of

the curve, thoracic,

lumbar,

or thoracolumbar;

the direction of the curve, left or

right; and the angle of the curve. The

degree of each curve is measured by

the Cobb

method (see figure 2). The Cobb

method determines the angle of the curve

by measuring the angle between the two

most slanted vertebrae (Lonstein, 1999).

Scoliosis is identified as a curve larger

than 10 degrees, regardless of spinal

level.

According to the Mayo Clinic, when

considering treatment, physicians look

at six different risk factors for progression

(Staff, 2007). The first of these factors

is growth. A growth spurt often worsens

an existing curve. A second factor is

sex; scoliosis in girls is more likely

to worsen than scoliosis in boys. The

age of a child also contributes to the

progression of a curve. If a child is

very young when scoliosis is identified,

chances are the curve will increase.

Size of the curve is a fourth factor:

the larger the angle of the curve, the

more likely that it will worsen.

The location of the curve also determines

the potential for progression. Curves

in the thoracic region are more likely

to worsen than those in the lumbar or

thoracolumbar region. A final determinant

for progression is whether there were

spinal problems at birth. Congenital

scoliosis is more likely to progress

than other types of scoliosis.

Treatment for scoliosis is based mainly

on the degree of the curve, how quickly

the curve is progressing, and where

the child is in their growth spurt.

According to Lonstein (1999), “If

a curve is less than 20 degrees, an

increase in the curve of 10 degrees

or more is required before bracing is

started. A 20 – 29 degree curve

must change by five degrees before treatment

is initiated. A curve between 30 and

40 degrees requires immediate bracing

if the child is still growing. If a

curve is between 40 degrees and 100

degrees, surgery is typically indicated

(p. 599).”

There are three types of braces commonly

used in scoliosis, the Boston

brace, the Milwaukee

brace, and the Charleston

Bending brace. Bracing is only effective

if the skeleton of the child is not

mature. For girls, the skeleton is mature

between the ages of 15 and 16 years,

and for boys the skeleton is mature

between the ages of 17 and 18 years.

The Boston

brace is also called a thoraco-lumbo-sacral-orthosis,

and is often referred to as an “underarm”

brace. This brace works by applying

three points of pressure to the curve

to prevent progression. The most common

application is for curves in the lumbar

or thoraco-lumbar spine. The brace is

made out of hard plastic that has been

molded to the child’s body. It

is worn 23 hours a day, but can be removed

for gym class, swimming and other sports.

The Milwaukee

brace is a cervico-thoracic-lumbo-sacral-orthosis.

This brace looks like the other brace,

but has a neck ring that is attached

to the body of the brace to hold it

in place. Like the Boston brace, this

one is worn 23 hours a day and can be

removed during the day for physical

activity. This brace is suggested for

thoracic spine curvatures. A final brace

is the Charleston Bending brace (figure

4).

The Charleston

brace is molded to the child’s

body when they are bent toward the convexity

of the curve, thus applying more pressure

to the curve (McAffee, 2002). Because

the brace is only worn at night, many

self-esteem issues are avoided. Self-consciousness

due to wearing a brace at school, or

a student’s friends “finding

out” is avoided. This brace is

recommended for curvatures of 25-40

degrees with the apex of the curve below

the height of the shoulder blade (McAffee,

2002).

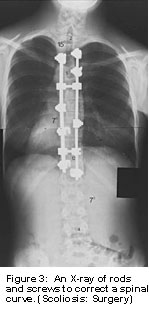

Surgical

intervention is required for curvatures

between 40 degrees and 100 degrees.

According to the Mayo Clinic, “Scoliosis

surgery is one of the longest and most

complicated orthopedic surgical procedures

performed on children (Scoliosis: Surgery).”

The operation lasts approximately six

hours and requires a 5-7 day hospitalization.

Mayo clinic surgeons perform a posterior

spinal fusion that uses a modified two-rod

system originally invented in 1984 by

two French surgeons. The rods and screws

are attached to the spine in an effort

to correct the curve as much as possible

(figure 5). Part of the spine fuses

to maintain the correction. The hardware

is not removed, even after the fusion

is healed. A person’s movement

may be slightly altered. Surgical

intervention is required for curvatures

between 40 degrees and 100 degrees.

According to the Mayo Clinic, “Scoliosis

surgery is one of the longest and most

complicated orthopedic surgical procedures

performed on children (Scoliosis: Surgery).”

The operation lasts approximately six

hours and requires a 5-7 day hospitalization.

Mayo clinic surgeons perform a posterior

spinal fusion that uses a modified two-rod

system originally invented in 1984 by

two French surgeons. The rods and screws

are attached to the spine in an effort

to correct the curve as much as possible

(figure 5). Part of the spine fuses

to maintain the correction. The hardware

is not removed, even after the fusion

is healed. A person’s movement

may be slightly altered.

A second type of surgery that Mayo

clinic surgeons are investigating is

for early onset scoliosis (Scoliosis:

Surgery). This technique uses “growing

rods.” Two parallel rods are attached

at each end of the curve. As the term

“growing rods” implies,

the center of the rods are adjustable

as a child grows. The lengthening of

the rods is done during outpatient surgery.

This surgery helps prevent heart and

lung difficulties associated with early

onset scoliosis.

Other treatments for scoliosis include

neuromuscular electrical stimulation

of muscles, chiropractic manipulation,

and physical therapy. Limited information

is available on the use of these methods

to treat or prevent scoliosis. Clinical

trials using neuromuscular electrical

stimulation of muscles alone to correct

a scoliosis curvature, or to prevent

the progression of a curve, have not

been published. A type of trial published

in a 2001 issue of the Journal of Manipulative

and Physiological Therapeutics reports

in their study, spinal manipulations

alone, “…were not effective

in the correction of curvature of scoliotic

spines… (Lantz D.C. & Chen

D.C., 2001).”

However, a case study done by Kao-Chang

Chen, M.D. and Elley H.H. Chiu, M.D.

in The Journal of Alternative and Complimentary

Medicine used chiropractic manipulation

to decrease a Cobb angle of 460 to 300

in a 15 year old girl after 18 months

of intervention (p. 749). A literature

review by Martha C. Hawes, published

in Pediatric Rehabilitation “…supports

the hypothesis that exercise-based therapies

can be used to reverse the signs and

symptoms of scoliosis in children and

adults (p. 178).” The review also

points out that, “…there

does not appear to be a single study

supporting the dogma that scoliosis

will not respond to exercise-based therapies

applied early in the disease process

(p. 178).”

Physical activity is not limited for

adolescents with scoliosis that are

receiving brace treatment, physical

therapy, or chiropractic. The brace

can be taken off for physical activities

that require more flexibility, or for

contact sports or swimming. Physical

activity is only contraindicated for

adolescents that have had surgery. Each

doctor will likely have their own protocol,

but the Mayo Clinic’s protocol

for post-surgical fusion follows these

activity guidelines. Post-surgery includes

a restriction of activities for several

days, and a restriction from physical

activities like running and gym class

for three months after surgery.

According to the Mayo clinic’s

protocol, patients can return to normal

activity excluding gym class, diving,

contact sports, horseback riding, amusement

park rides and lifting more than 25

pounds after three months (Scoliosis:

Surgery). After six months, the patient

can rejoin gym class and participate

in all activities except contact sports

with their doctor’s permission.

One year after surgery without complications,

and with their doctor’s permission,

a patient can return to full activity

including contact sports.

Although the literature supports varying

theories on the effectiveness of bracing,

surgery, chiropractic manipulation,

and physical therapy, it seems clear

that most adolescents with idiopathic

scoliosis can lead a full, active life.

Children with scoliosis can participate

in school sports, recreational sports,

and individual activities during treatment

for scoliosis. And students that have

surgery to correct a scoliosis curve

can resume participation in most activities

after six months and full activity after

a year.

Works

Cited

Chen, K.-C., & Chiu, E. H. (2008).

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Treated

by Spinal Manipulation: A Case Study.

The Journal of Alternative and Complementary

Medicine , 749-751.

Hawes, M. C. (2003). The use of exercises

in the treatment of scoliosis: and evidence-based

critical review of the literature. Pediatric

Rehabilitation , 171-182.

Lantz D.C., C. A., & Chen D.C.,

J. (2001). Effect of Chiropractic Intervention

on Small Scoliotic Curves in Younger

Subjects: A Time-series Cohort Design.

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological

Therapeutics , 385-393.

Lewis, R. A. (2008, February 27). Medical

Encyclopedia: Scoliosis. Retrieved

March 22, 2009, from Medline Plus: http://www.nim.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001241.htm

Lonstein, J. E. (1999). Scoliosis update:

Managing school screening referrals.

Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine

, 593.

McAffee, P. C. (2002, March 26). Types

of Scoliosis Braces. Retrieved

March 28, 2009, from Spine Health: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/scoliosis/types-scoliosis-braces

Scoliosis: Surgery. (n.d.). Retrieved

March 28, 2008, from MayoClinic.com:

http://www.mayoclinic.org/scoliosis/surgery.html

Staff, M. C. (2007, December 14). Scoliosis.

Retrieved March 22, 2009, from MayoClinic.com:

www.mayoclinic.com/health/scoliosis/DS00194

Stopka, C., & Todorovich, J. R.

(2005). Applied Special Physical

Education and Exercise Therapy.

Boston: Pearson Custom Publishing.

Yochum D.C., T. R., & Maola D.C.,

C. J. (2008). Scoliosis. The American

Chiropractor , 14-16.

|